Joan Little and the Making of a Man

A story I'd forgotten that percolated within me for 50 years

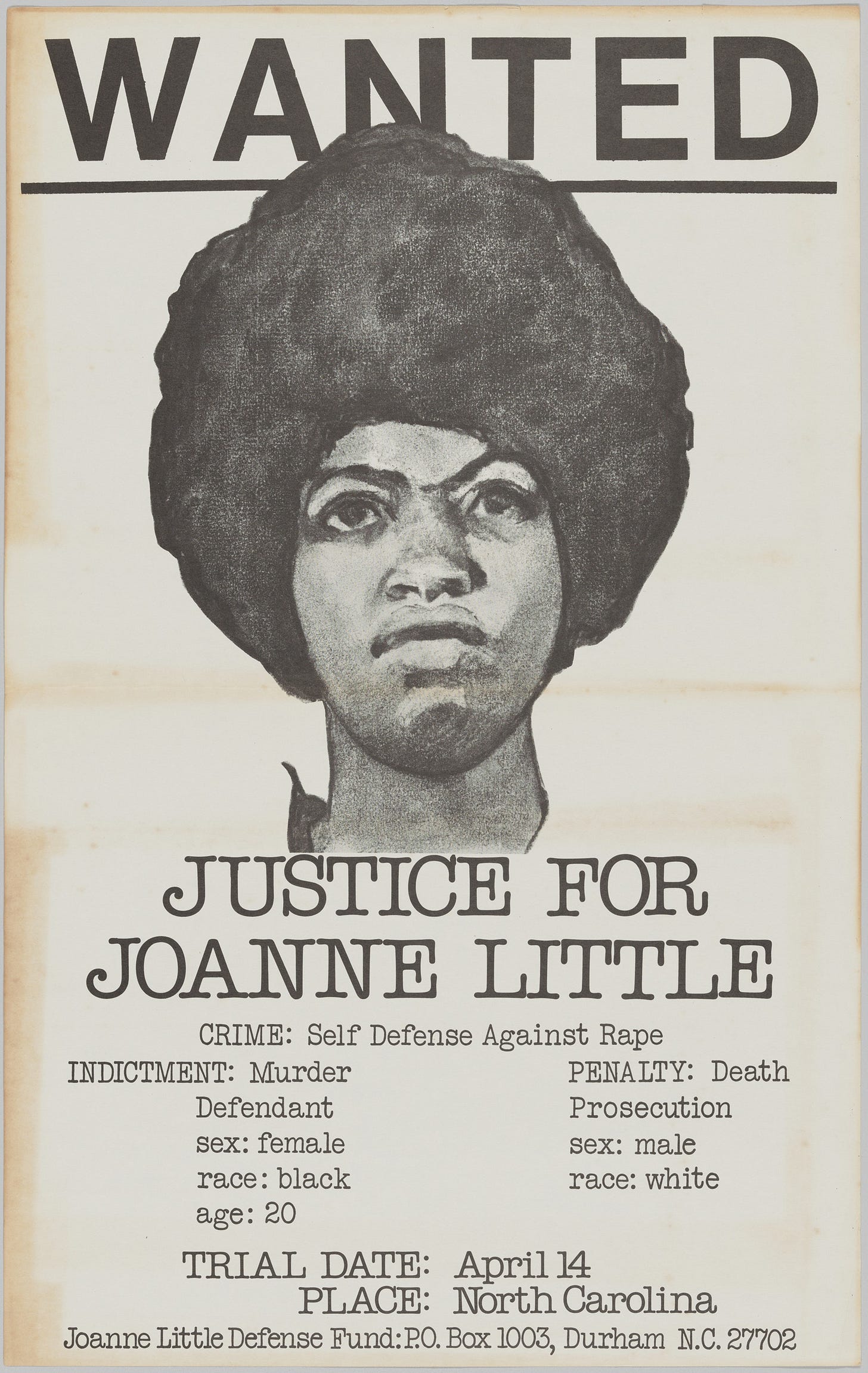

Tomorrow, August 15, marks the 50th anniversary of the acquittal of Joan Little by a North Carolina jury of six African-Americans and six whites.

When I saw her name pop up the other day while considering the history of racial bias in jury selection, I had only the vaguest, cob-webbiest contemporaneous recollections of her. Honestly? All I recalled without aid of the Internet was a big news story that played in the background of my tween years involving a Black woman as a defendant in some sort of criminal case. I cannot presently recall knowing more back then, although I'm sure I knew much more about it at the time. There's just no telling now how much more beyond that I was exposed to - let alone how I processed that information.

Oh, wait, you may need a refresher course like I did: who was Joan Little to America?

I had to look it up myself. Here’s a synopsis from the Washington Area Spark:

Little was jailed for minor crimes in the Beauford [sic] County, NC jail. On August 27, 1974 white guard Clarence Alligood was found dead on Joan Little’s bunk naked from the waist down with stab wounds to his temple and heart. Semen was later discovered on his leg. Little turned herself in a week later and claimed self defense against sexual assault but was charged with first degree murder. The case attracted national attention in part because Little would have received the death penalty if convicted. … Little may have been the first woman in United States history to be acquitted using the defense that she used deadly force to resist sexual assault. Her case also has become classic in legal circles as a pioneering instance of the application of scientific jury selection.

Since I ran into Joan Little earlier this week, I’ve been obsessing over what was going on across America at the time of her trial - because it is surreal to think that as late as 1975, this was an historically successful use of rape as a defense to murder.

I recall that her case came up in conversation at home in New Jersey. After all, at dinner - and beyond - we talked about the stories in the news. I also know those conversations would have only taken place in hushed tones to shield me from having to hear the word "rape" - or understand what it entailed. I feel pretty sure in the mid-70’s, “rape” was only uttered cautiously in conversation and in news and entertainment circles. I believed that the topic of rape and sexual assault was just finding its way into the zeitgeist. That was a difficult observation for me to recall because I might just as easily attribute its increased usage to my age, and the fact that it was around this time that I was finally allowed to go to PG movies.

A deeper dive into the cultural time machine suggests that much of my recollection is accurate: it was around this time that the news started to report on rape, calling it by name. And fictional stories - like daytime serials - started to build it into storylines, leaving out suggestions that it was in some way a romantic device. Slowly, news and fictional accounts portrayed rape occurring among people who were proximate, before and after - and that it wasn't a random mugger or a strung out junkie waiting for the first opportunity while hiding in a dimly lit alley who'd then vanish into oblivion.

That was a wild time. The public had these confidently-held gross misconceptions while those who experienced rape and sexual assault - as well as those who practiced it - knew otherwise.

And as rape was given a more frank portrayal in news and entertainment, it seems that people started to talk about rape - and, as that happened, public perceptions, slowly, seem to have inched closer and closer to reflecting the lived reality as, more and more, the public perceptions were informed by those who understood rape as a lived experience.

Luckily, as a function of my age, I was shielded by etiquette and decorum from having the gross misconceptions drilled into me prior to the mid-70’s.

Yet Joan Little was not the kind of person that the culture recommended to me, a white kid in New Jersey, as a reliable source for wisdom. She was Black. She was poor. She was part of “the criminal element.” And, although I was too young to know this next part, the fact that she was raped attached the added stigma of “loose morals” to many of the adults around me. In my world, these would count as strikes against her credibility. They made her, in my white suburban orbit, unlikely to receive empathy.

At the time her case was making headlines, her version of what happened was teed up to be disqualified - an unfortunate reality that Clarence Alligood registered as an opportunity.

Yet she was acquitted.

I think, partly because of Joan Little, America was crossing a demarcation point in its timeline that spit out a different version of myself from the one that might have entered adulthood if the culture hadn't begun to take the turn it did when it did.

Attitudes have shifted with time, with varying rates of progress toward centering and accepting the voices of the most profoundly impacted people when we seek to understand our world. America has never been at the place where, for so many reasons, the likes of Joan Little would be believed, notwithstanding the outcome of her jury trial. On a societal scale, we’ve never worked out who to trust and who to distrust.

We might be tempted to take solace that the arc of the moral universe is at least heading toward justice…but is it?

If we've learned anything over these recent years, history does not automatically flow in one direction. There's no guarantee that humanity or society or culture will “improve” over time. Our DNA doesn't change or improve. We bend history in one direction or another, until we bend it in a different direction.

More and more I'm seeing the expectations and obligations and attitudes that too many men (and even too many women) have about sexual consent, bodily autonomy, and the roles of women being bent backwards (from my frame of reference) to a benchmark that predates the attack on Joan Little. (And, yes, I gendered that observation because another observation worth noting is that I don't see NB and queer folx reversing course to reclaim an historical safe space for repressing vulnerable people.)

During high school and college, in the late '70s and early '80s, I worked summers and holidays in a high-browed office in Manhattan. The secretaries, ranging in age from their late 20s to early 60s, took me under wing. They introduced me to various international cuisines and street vendors I would have skipped over. Knowing I was heading to college, and later to law school, they coached me on what makes a bad boss and what makes a beloved boss - critical legal training for which I paid no tuition. But - in retrospect - they also coached me on how to treat women - and how to not be a monster, of which they all had stories to tell me. Only now am I wondering if these lessons they shared with me could have been spoken - and believed - before Clarence Alligood got himself killed.

Nowadays, for all the “progress” we’ve supposedly made, I get on-line and take some wrong turns on social media (not even coming close to the Dark Web) or, when I peer down the long, stuffy corridors of economic and political power - or even if we just reflect on the resident at the U.S. Naval Observatory, the residence of America’s Vice President, J.D. Vance - and more and more what I see coming into view is a long parade of young men channeling the spirits of those monsters of the past.

If the arc is a one-way street, then why do I see more of the kinds of horrid people the secretaries told me about in the late ‘70s - people who have expectations and impressions about women that deny them agency and are informed by violent thoughts? Their attitudes blow my mind, thankfully, on account of my being fortunate to have come of age on this side of Joan Little's acquittal.

I didn’t know it all this time, but I think tomorrow is a big day for me. Count me as someone who is tardily grateful for Joan Little.

(More below the photo)

FURTHER READING

One of the richest sources of information that I found on Joan Little’s trial, or what I recommend as your first stop if you’re ready to visit the Joan Little rabbit hole, is here: https://www.blackwomenradicals.com/blog-feed/in-defense-of-black-women-the-case-of-joan-little

For a time machine look at Joan Little, consider this republication of Angela Davis’ contemporaneous account of the case, from Ms. Magazine : https://msmagazine.com/2024/03/05/joan-little-dialectics-of-rape-june-1975/

Here’s a moving account by Karen Bethea-Shields, one of Little’s lawyers: https://www.ncpedia.org/listening-to-history/bethea-shields

This is a quick read but it covers some details of her early life as well as some post-acquittal information about Joan Little: https://alchetron.com/Joan-Little

For those also interested in how attitudes have shifted over time - “what were those people thinking back then? - this October 2011 paper from the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence offers both an overview of shifting narratives as well as suggestions and tools for continuing to shift them, plus a long bibliography to explore: https://vawnet.org/sites/default/files/materials/files/2016-09/AR_ChangingPerceptions.pdf

I believe the Joan Little case - and her acquittal - opened the door to reconsider other false narratives and trust along (i) racial lines, (ii) economic classes, (iii) prison abolition and carceral stigmatization, and (iv) perhaps even age, as she was only 20 at the time. As much as I’ve focused here on how it helped fuel the debunking of myths and perceptions about rape and sexual assault, I can see how it may have given myself, if not the nation, an opportunity to shed some of the weight dragging me down in the form of biases that I consumed as a regular part of my multimedia diet. I’m not suggesting I then raced through any of these portals - but if you have some suggestions for reading on how those other false narratives have changed (or haven’t changed) over the past half-century, I’ll welcome your offerings in the comments.

Such a moving account of how cultural shift can help shape us. It demands answers to the critical question of how we can counteract the toxicity of current cultural shifts. I can't suggest answers on how to stop regression except to keep communicating and advocating for understanding and compassion in the face of arrogant ignorance.

And thanks for the references. Angela Davis' article is earth-shakingly good. I own a copy of the very first (Spring 1972) issue of "Ms.," joyfully received by young women in my circle. At my first job as a college graduate in Manhattan, I still remember buying it at a newstand on my way to the subway home. Among the articles, some of which stood as minor classics of U.S. feminism, there was indeed no mention of rape or violence against women.